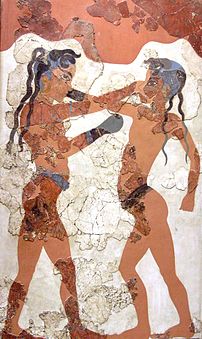

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

- William E. Vaughan

The world of martial arts is full of arguments based on irrelevant appeals. From advertising campaigns that argue their style of martial art is the best because it is practiced by a certain country’s elite military to teaching techniques a certain way because this is the way they have been taught for centuries. They are arguments that do not provide evidence to support their claims, but instead use information designed to make you feel inadequate in your questioning. I shall now take you through some examples of the way appeals arguments, “Martial Appeals” if you like, are used as a method of one-upmanship from one martial arts stylist to another, as a form of persuasive marketing or to simply keep control of the way a student thinks.

Appeals to Antiquity or Tradition

The age and durability of an idea is not always an accurate indicator of its value. However, it is very common for a martial artist to somehow connect the antiquity of their system or style with practical efficiency. The reasoning goes something like this: if these moves or practices didn’t work then they wouldn’t have survived. This is nonsense. There are plenty of reasons why impractical and illogical practices are still being carried out today. Many people cling to rituals out of a sense of national or cultural pride. Traditions are often kept so that people feel they have a link to the past. Some people even have their own personal rituals and in extreme cases these can be strong indications of different types of mental and neurodevelopmental disorders. People also fear change, as it presents the prospect of the unknown. Tradition and the illusion of not changing make us feel safe.

An example I once saw was the historical evidence that martial arts have often been linked to magic. This is not surprising, studies have shown that the closer people come to the presence of death the more superstitious they become. In this particular example, the argument was made that even the most sceptical person must concede that there must be something practical in this connection since there is such a long tradition of it happening. This is a classic example of a jump from one set of information - valid historical evidence linking the belief in magic with martial arts practices – to another – therefore it is possible that magic is a part of martial arts. The first set of information does not provide evidence for the latter. There are very long traditions of the belief in monsters found in most cultures, and fairly often different and completely unrelated cultures come up with very similar monsters. This is not evidence that the monsters existed, but probably has more to do with the limitations of human imagination and common innate fears and the superstitions we create around those fears.

The age of a martial arts system is often held in disproportionately high regard despite the obvious advancements made in combat technology. We know old ideas are not always good ideas otherwise we wouldn’t have any progress. In a relatively short amount of time there have been major advancements in what we know about human anatomy, the way the human brain functions, human behaviour and human potential. We also have the hindsight of history to determine how an old idea might not work. It is far more productive and sensible to question why an old idea has persisted than to make positive assumptions about its validity.

Appeals to Authority

As one would expect those who often use the appeal to antiquity or tradition are those in positions of authority. However, often a person of authority is presented as the actual justification for an argument: Hanshi so-and-so said this is the deadliest of all martial arts therefore this must be true. Like the appeal to antiquity or tradition argument, if we just took the words of experts as gospel we would make no progress. Science constantly questions and advances the work of its great innovators understanding that their work needs updating. It is also worth keeping in mind that someone might have more knowledge on a certain subject than their critic, but their method for applying that knowledge might be deeply flawed.

The other issue regarding appeals to authority is when the authority is not an authority on the topic of the argument. For a long period it was common for most martial arts schools to specialize and, even with the advent of more liberal and open dojos, dojangs, kwoons and gyms most schools still do. However, I recall seeing a journalist asking a boxing coach’s “expert” opinion on a mixed martial arts bout. Unsurprisingly the coach’s response was negative and despite the bout being regulated by strict rules, clearly watched over by an experienced referee and a medical team on hand, the boxing coach compared it to a street-fight. Nevertheless, this authority was a respected and qualified boxing coach running a high performing boxing club. His validity for teaching his sport is not in question, however, his opinion on something that he had little knowledge on had about as much relevance as an ice skating coach discussing the form of a champion skier. Now, if the person being consulted on the mixed martial arts bout was an experienced doorman who had seen thousands of street-brawls and made the same comparison that would have been a different matter.

Appeal to Popularity

By the time the 1980s started the “Kung Fu Boom” was over, however, martial arts had clearly taken root in the public consciousness and a corporate side slowly began to emerge. As this spread and more organizations and governing bodies began to pop up all over Europe and the USA, the marketing machines picked up pace. This was more than a few clubs being affiliated to a foreign authority now; whole associations broke away in the western world and grew into their own entities. It wasn’t long before this corporate image was used as part of the advertising gimmick and, as always, size mattered. Clubs, instructors and individual students were encouraged to join the association with the most members. Popularity has a strong appeal. In military and political thinking we can see an obvious advantage of being on the side with the biggest numbers. Popularity is also at the heart of fashion and retail. However, just because an idea is popular it doesn’t mean it is right.

Popular opinion can, and often is, swayed by charismatic and persuasive personalities. History has certainly told us this many times. In martial arts we have seen many trends promising much and often delivering little. Talk to any long term martial arts magazine editor and they will tell you plenty about the various phases and sub-phases of martial arts. In hindsight a craze in a certain martial art often had little to do with the art’s efficiency, but rather the way it was being sold to the general public.

Appeal to Novelty

The opposite of the appeal to antiquity or tradition is the appeal to novelty. The newness of an idea does not automatically make it the superior of what has gone before. There are many new martial arts systems springing up all the time. Not everyone likes to cling to tradition or popular systems, many like the idea of being up-to-date or being different.

One argument here is that this martial art is new therefore it will provide me with information more applicable to the modern world. Just because the system is new it doesn’t make it better suited for the modern world. It could endorse pseudoscience or have no proper basis on efficient training methods whatsoever. There are plenty of new bogus martial arts popping up all over the place, often promoted by the technology that is synonymous with our era: the internet.

Another argument is that a certain martial art is different and therefore better than more conventional martial arts. A key appeal of the oriental martial arts in the western world was their sheer exoticness. Therefore it should be no surprise that within the martial arts world there is always a strong attraction towards more unusual martial arts. However, many previously unheard of martial arts have little historical evidence to back up their lineage or even their validity. There are some societies that are unashamedly resurrecting extinct martial arts and honestly doing their best to interpret these old training methods out of historical interest. There is nothing wrong with these practices. However, there are still others that exploit the gullibility of enthusiastic martial arts tourists and those members of martial arts subculture who have a natural disposition towards learning something that is marketed as being “forbidden” or “forgotten” or simply out of the mainstream.

There is no rational basis in arguing that just because something is new or different that it is any better than what is old or commonplace. In fact, in all rational fact-finding disciplines from science to history the burden of proof is always placed squarely on the shoulders of the new or unusual idea.

In conclusion, if we are to get the best out of the martial arts we can do better than appeal to irrelevant information. By recognizing these types of arguments not only in others but also in ourselves we can focus more on addressing a problem or question than trying to win a debate or live in denial. Don't forget to check out Jamie Clubb's main blog www.jamieclubb.blogspot.com

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=7aa52516-a088-41e9-a89b-975ced48cff6)